An exhibition at The Foundling Museum in London that features incredible artwork from the last 500 years depicting pregnant women has just re-opened following lockdown. The works are rare – pregnancy was not commonly featured in portraits – and extraordinary. We find out more from the curator, Karen Hearn.

(Top; Textile Panel with Embracing Figures, c.1600 © Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford, Right; Marcus Gheeraerts II Portrait of a Woman in Red, 1620 ©Tate )

The museum has re-opened with COVID-19 guidance in place for visitor safety so please do take a look before you visit.

The show features portraits, and it specifically focuses on women depicted during pregnancy. This has never been done before, especially in a show of portraits.

We have primarily British portraits. But there is some international art with Demi Moore on the cover of Vanity Fair in 1991, and the globally iconic image of Beyoncé announcing her pregnancy on Instagram.

At the Tate Gallery, I was the curator of 16th and 17th century British art. About 20 years ago, we acquired a painting from about 1595 of an unknown Elizabethan woman.

There was one thing about it that was incredibly obvious, but that wasn’t mentioned in the paperwork. It was that the woman was very visibly pregnant.

I was fascinated that people who had written about the picture didn’t mention the pregnancy.

But ironically, we know that in the past many women were constantly pregnant. A woman in one of the portraits reproduced in the book that accompanies the exhibition, called Catherine Carey, Lady Knollys, had between 14-16 children and died in her 40s. This was in 1562.

What I’ve realised is that these portraits offer us a different lens through which to look at history. A chance to think about those women conducting busy, public and social lives, while being constantly pregnant.

Or after all those children, they might have had prolapses or heaven knows what. It’s something that hasn’t really been thought of. It makes us consider history in a different light.

We believe it’s because a woman who is visibly pregnant is clearly sexually active. And that wasn’t the view of women that society was comfortable with. The women in this exhibition are mostly married women. Even though their husbands paid for the pictures and everything is within the constraints society wanted, talking about pregnancy and showing pregnancy, was problematic.

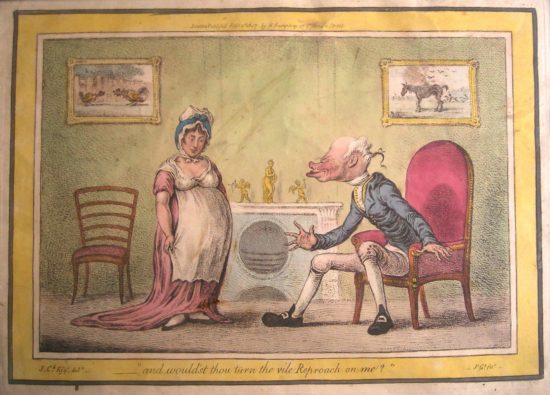

By the 18th century, we have stopped seeing a pregnancy depicted but we start to get more information. Artists like Sir Joshua Reynolds or George Romney would have sitters’ books. These books were diaries with their professional appointments listing who was ‘sitting’ for them to be painted.

Theresa Parker, wife of the future Lord Boringdon, a landowner, was painted in February 1772, and gave birth in May 1772. The dates show she was pregnant at the time that she sat for her portrait; but you don’t see this in the painted image.

She and her husband were redecorating their country house in Saltram in Devon. Her husband wanted a full-length portrait of her to match a family portrait of a male ancestor of 150 years earlier. He couldn’t wait, and wanted her to sit while she was pregnant.

Her sister wrote in a letter that although it might seem “improper” that she was sitting to Sir Joshua at this time, Sir Joshua had said that it was fine, and that the benefit was that she looked so “fat in the face.” Although the implication is that this is a good thing, we also learn that Sir Joshua had told her that he would concentrate on her face and would paint the rest of her body later.

Only from the early 20th century, and then only in bohemian circles. We have Augustus John’s portrait of his wife, Ida. He met Ida at the Slade Art school and she was there six years, so she presumably intended to have a serious artistic career.

They married at the beginning of 1901, and she became pregnant quite quickly and had a son. In the end, she had five sons with Augustus. She died after giving birth to the fifth son, in 1907, from a mixture of peritonitis and puerperal fever. It’s tragic, and she never had time between children to pursue a career in art.

Figurative artist Ghislaine Howard’s picture of herself in 1984 was made quite late in pregnancy. Her normal practice was to paint herself standing up, but she was so heavily pregnant with her first child that she sat down. I notice people coming in and when they see it they just say: “Oh, I felt like that.” I hunted that image down.

Then we get to Vanity Fair and Demi Moore, and that’s really when nudity during pregnancy becomes publicly visible. I’m not saying there weren’t previous portraits of nude women, but very rarely showing pregnancy.

We end with the picture of Beyoncé from February 2017. She announced that she and her husband were expecting twins with this image. Portraits are a matter of choices, and the choices result from discussion between the artist, the sitter, and the person who is paying. In this case, people think of it just being Beyoncé, but it’s actually by the artist Awol Erizku.

But of course the thing is that it’s Beyoncé in control, which is different from other pictures of women in this exhibition. Certainly, Lucian Freud’s wife is arranged and isn’t very happy in 1947. But Beyoncé is in control, she’s the person credited with it, she puts it on social media; she’s in charge.

Going into the exhibition, dead ahead is the Hans Holbein drawing of Thomas More’s daughter, Cecily Heron. I think that’s my favourite. It has been lent by Her Majesty the Queen, and it’s a fantastic opportunity to see it.

It’s extraordinary, because Holbein had been commissioned to make a group portrait of Thomas More’s family. He sketches all the individuals’ heads and upper bodies, and then puts them together to make the group picture.

The purpose of that sketch is just to record what he sees. He records her incredibly intelligent face, very clearly and directly, as well as her body, and because she’s pregnant and her bodice is loosely laced, he records that.

We’re in direct contact with the way that a woman 500 years ago would be dealing with her pregnancy.

The subject has not been tackled before, amazingly, and we’ve got this extraordinarily interesting narrative, over 500 years. Not to mention, that many of the pictures are of top quality.

We’ve got a beautiful Van Dyck portrait which comes from Claydon, the country house in Buckinghamshire. There’s also the amazing Lucian Freud of his wife, which is a fantastic loan.

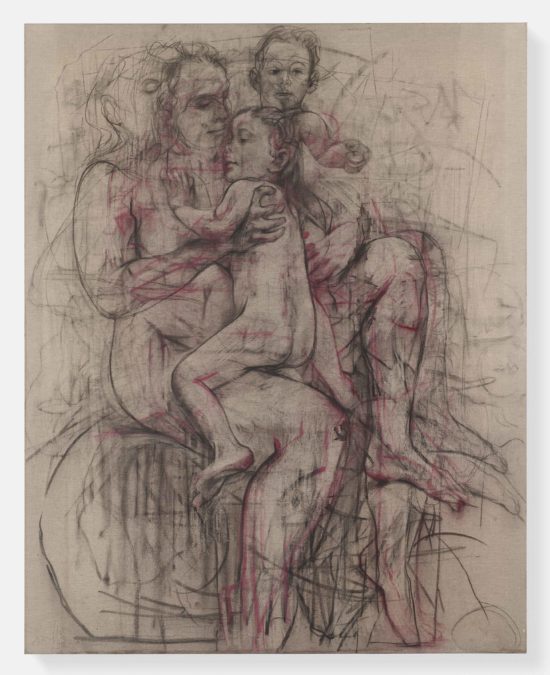

The Jenny Saville piece is getting a lot of attention. Jenny Saville is one of the notorious 90’s Young British Artists, who now has two children. She’s very influenced by Leonardo da Vinci’s large drawing in the National Gallery, of The Virgin and Child with St Anne and St John the Baptist. She often references that picture, and completed this for our exhibition. She started it in 2012 but she finished it just before Christmas – so it’s never been seen before.

We have on display a painting of Princess Charlotte, who died in childbirth. We also have the actual Russian-style dress from about 1817 that she was wearing in the picture. It’s on loan from Her Majesty the Queen.

It gives you a real frisson to see a garment in a painting, then to see the actual garment. You’re immediately in touch with that girl. Because she died there was no heir to the throne, so had she lived, Queen Victoria would not have existed. The middle-aged sons of George III had to get rid of their mistresses, and find suitable German duchesses to marry.

The one who succeeded in having a child was the father of Queen Victoria. All because poor Charlotte and her baby died in childbirth. So these are Grade A works of art. And a fascinating insight into women’s history and place in society during this time.